“The more troubling aspect is not that Germany is currently about 30% behind the United States in GDP per capita terms. What concerns me more is the relative deterioration over just one generation.”

That is an excellent point raised by my friend Detlef in a comment on my previous post (thank you, Detlef!), and one I should have addressed. It captures where a lot of the Sturm und Drang comes from among politicians and pundits in Europe in the face of US economic “outperformance” as measured in per capita GDP. It’s not the absolute difference in terms of GDP per capita, it’s the trend that counts, and that trend is deterioration.

Detlef’s concern motivates an overall narrative (which I won’t ascribe to Detlef) that European countries like Germany are in decline relative to the US because they are over-regulated and over-taxed, and because the US works harder, with more creativity and risk-taking. While Germany tied itself up in regulatory knots to prevent climate change and taxed its Macher (“movers and shakers”) to death (or into exile), the US unleashed Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, and Sam Altman to bring about the 4th Industrial Revolution.

Or so the story goes.

It’s a satisfying narrative for those in the US who like to self-congratulate and for those in Germany who’ve been brought up to self-flagellate. There may be a kernel of truth to it, as there must always be to any narrative that resonates. But the data don’t support it. Let’s look at the trend.

I’m going to use 1995 as a baseline for the trend comparison. Partly because it’s a neat 30 years. Partly because it corresponds nicely to the dawn of my own economic awareness. And partly because it corresponds roughly to the “information age.”

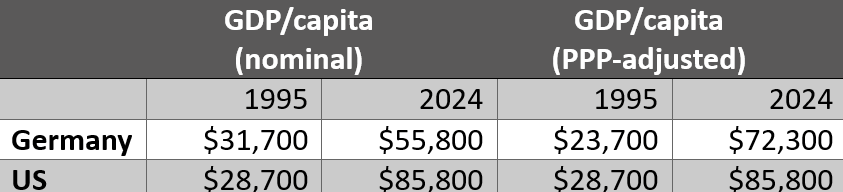

When Detlef wrote that “Germany is currently about 30% behind the US in GDP per capita terms” he is – like Yasha Mounk – referring to raw GDP per capita numbers: $55,800 versus $85,800 (2024; all figures sourced from the World Bank database again unless otherwise indicated). And indeed, if you look at 1995’s raw numbers, Germany had higher per capita GDP than the US: $31,700 versus $28,700.

But these figures ignore relative pricing levels. When you take pricing levels into account, you see that Germany’s per capita GDP was actually lower than the US’s: $23,700 versus $28,700 (the US’s price level is used as the reference, so the US’s PPP-adjusted per capita GDP is identical to the un-adjusted value). That’s a difference of 21% — 21% higher PPP-adjusted GDP per capita in the US in 1995 than in Germany.

Today that difference in PPP-adjusted GDP is 19%: PPP-adjusted GDP’s per capita of $72,300 versus $85,800. So while the average American is “richer” than her German counterpart, that was also the case 30 years ago, and if anything, Germany has “caught up” slightly.

Poof goes the narrative.

But how can this be? Didn’t Silicon Valley change the world while Germans took six-week vacations and called in sick whenever they sneezed more than twice in two minutes? Didn’t tech superheroes enrich our lives with free maps and on-demand-streaming while German engineers dithered around with obsolete internal combustion engines?

Part of the narrative is that American job-creating maverick entrepreneurs broke all the rules and created a crazy new world in which high-paid coding wizards cruise to work in their self-driving Teslas and then return to the kinds of glam downtown apartments you see on Friends and Sex in the City. But those rule-breaking mavericks may have destroyed a bunch of industries and jobs as well. It is called creative destruction after all. It’s not a given that technology makes people richer in aggregate, though it may make individual people rich.

But what’s important to understand about the information technology sector is that – whatever impacts on GDP per capita it might have – those impacts have not been disproportionately recorded in US GDP, or not wildly so. The consumption of those goods and services, the labor used to produce them, the supply chains of the IT industry, and even the financing are all globalized. At the end of the day, America can claim some bragging rights for birthing brands like Apple, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft, but in terms of GDP contribution, the value creation is spread all around the world. So while the tech sector may have generated a lot of GDP growth it will have done so globally.

The healthcare sector is a different beast. Its value chain is much more domestically based. Both the US and Germany have experienced disproportionate growth in their healthcare sectors – annual growth higher than GDP growth – since 1995. The sources I found indicate growth of 268% and 477% of growth in health spending, respectively in Germany and the US (caveat: I cannot tell from either source whether these numbers are adjusted to the respective countries’ inflation rates).

Both countries have seen their populations age over those three decades, though Germany’s more so. So given that Germany is older, and given that the US’s health outcomes are worse, it is strange that the US’s economy has become so much more dominated by the healthcare sector than Germany’s has. I can’t help but see this as a literally “unhealthy” development.

It certainly invites a different narrative than the one about the job-creating innovators unfettered by regulations and taxes. Instead, it invites the story of a nation of nursing home attendants working themselves sick in order to pay the medical bills for their sickness. Not to mention their legal bills for suits against the insurance companies who denied them coverage, and the interest on their student loans for a degree in communications from the University of Phoenix.

There’s a kernel of truth to that narrative, too. Perhaps more than a kernel as my previous post tried to argue.

In any case, there is no good case to be made that Germany’s per capita economic position has deteriorated relative to the US’s over the last 30 years.

That does not mean that Germany is not at an inflection point now, and that it may need to do something – maybe even dramatic things– to adapt to an aging population and the decline of the internal combustion engine. But there’s no need for self-pity. And no need for Elon-envy.

Thanks for the thoughtful and data-rich response, Ruminathan. I agree that adjusting for purchasing power parity (PPP) gives a different long-term picture than the raw GDP-per-capita narrative often used in politics and media, and your point that the relative position has not worsened over 30 years is well taken, although quite self-serving (from a German perspective).

That said, I still see three concerns worth highlighting:

The International Monetary Fund has also cautioned against over-reliance on PPP for cross-country size comparisons, noting that “GDP in purchase-power-parity (PPP) terms is not the most appropriate measure for comparing the relative size of countries to the global economy, because PPP price levels are influenced by nontraded services, which are more relevant domestically than globally” (IMF spokesperson Jude Webber, Financial Times, 2011). While PPP is generally more robust than market exchange rates for welfare comparisons, it is not a neutral or error-free metric, and its apparent stability over time should be read with these limitations in mind.

I’d also reiterate my earlier point that averages hide as much as they reveal. Like-for-like comparisons—doctor to doctor, teacher to teacher, engineer to engineer—would give a sharper sense of where each economy is competitive in ways that improve everyday life. And in education, beyond PISA or Nobel counts, outcomes like patent productivity, SME innovation, and commercialization speed would round out the picture.

So while your analysis is a strong counter to the “Europe is falling hopelessly behind” narrative, we should remain cautious about over-relying on PPP stability as reassurance, given its methodological limits, the uneven quality of GDP growth, and the challenges ahead.

LikeLike