Across the developed world, hands are wringing vigorously about the sustainability of public pension schemes. Due to changing demographics, fewer and fewer workers will have to support more and more retirees.

What gets lost in the debates about the solvency of Social Security or similar programs is that the problem is not caused by the public nature of the scheme. Any conceivable private alternative would face the same underlying challenges. And those underlying challenges lie at a deeper level than demographic change.

Misfortune, senescence, and our long childhood

More than any other creature, we humans face a unique set of survival challenges:

- Misfortune: Our own productivity is subject to variation for reasons beyond our control, whether from illness, climate variation, or monetary policy

- Senescence: We are likely to live beyond our ability to provide for ourselves

- Long childhood: We arrive in this world unable to provide for ourselves, and we have to learn survival skills through a long phase of cultural transmission.

To address these challenges, working adults have to produce surpluses. We have to produce more goods and services than we can consume, and we have to find ways to store the surplus against both rainy days and old age. But no matter how productive we are, and no matter how ascetically we live, we cannot individually store enough food, water, shelter, medical supplies, etc. to get by for more than a few months, maybe a year at best.

At its simplest, we solve the problem with the intergenerational compact in which working adults provision their elderly parents while raising their own children. But we’ve always mutualized that compact beyond our immediate bloodline. Whether as hunter-gatherers, pastoralists, agriculturalists, industrial workers, or knowledge workers: We have always had to throw ourselves at each other’s mercy, paying forward some of what we don’t consume today. In turn, we look to others to provision us in our times of need. “What goes around comes around” is our great hope.

Project Civilization has been about creating institutions to buttress that hope. Central distribution hubs to store food (aka cities). Credit contracts and written records thereof. Private property. Insurance. The thing we call “money.” All those institutions are grounded in our collective will to allow a state to enforce these arrangements. With rule-bound violence if necessary.

Because it’s ultimately the state’s enforcement capacity that keeps our hopes credible, we’ve even short-circuited these institutions and have asked the state itself to collect and redistribute surpluses. That’s what public pensions like Social Security do. And that’s equally the premise of publicly funded education for our children and income security programs such as unemployment insurance to handle misfortune.

It doesn’t matter which mechanism we use: Whether collected by the state, saved in money, or invested in private enterprise, without surpluses generated by others there is nothing to store and nothing to distribute.

Demographic change: cause or effect?

The problem with our pension systems is not in how they are financed. The problem is that the working age population may not produce enough surpluses to simultaneously provision the retired and provision and invest in the next generation. It’s not about surpluses of money. It’s about surpluses of goods and services.

Economists speak of the age dependency ratio. There are different formulations thereof, but in its simplest form, it’s the ratio of the population under 15 or over 65 to the working age population between 15 and 65.

The naïve narrative about the looming crises in public social security systems is about demographic change. On the one hand, extended longevity has meant that people spend longer in the “retirement” phase where they cease to be net surplus generators. On the other hand, we are having fewer children, which means that there are fewer surplus-generating adults.

In the naïve telling, when we set up our public pension systems, we assumed our population would stay pyramid-shaped forever, with a few surviving retirees supported by an ever-widening base of new workers. In the US, the ratio of worker to beneficiary went from 3.3:1 in 1985 to 2.8:1 in 2021. I’m using 1985 as the baseline because that is 45 years after the first Social Security payment, so roughly when the system should have hit a steady state.

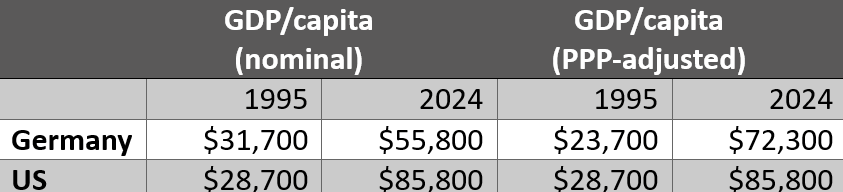

According to the mid-point projections, the US is headed towards a ratio of 2.1:1 in the next decades. In countries like Germany, with lower birth rates and lower immigration, the ratio is already 2:1, with projections taking the number of workers per beneficiary even lower.

The naïve story comes with naïve policy recommendations: People should work longer (US, Germany). We need “pro-natalist” policies incentivizing women to bear more children (US, UK). We should privatize social security (US, Germany).

And the ultimate policy recommendation is always: We have to increase productivity with our tried-and-true approach of greater labor specialization enabled by more technology.

The fact that the explanation of the problem and the recommended solutions are naïve (at best) or proposed in bad faith (at worst) is illustrated with two simple observations:

- The problem exists whether the mutualized surplus-storage solution is organized privately or publicly.

- Any system – public or private – built on indefinite exponential growth of the number of human beings on the planet is absurd from the get-go.

I would like to take the analysis of the underlying problem a step deeper than demographic change and the dependency ratio. I will show that causes and effects are intertwined, the policy measures miss the point, and “more technology” cannot always be the answer because it’s often the problem.

The intensification of child-rearing

Let’s start with another naïve observation. Fewer children should also mean fewer “unproductive” mouths to feed and more time available to generate surpluses. So on the face of it, having fewer children could also alleviate the problems facing pension schemes. In fact, economists speak of a demographic dividend that accrues when societies reduce their birth rates. This is a point we’ll return to a little later.

But having fewer children doesn’t necessarily mean we need fewer surpluses if the amount of resources dedicated to child-rearing intensifies. It’s one thing to have seven children when you live on a farm in a low-density settlement and can count on them to start contributing to farm production from a very young age. Or to have five children in a cramped one-room apartment in a high-density city if you can send them to shovel coal into a factory’s furnace, and that’s all the job that will ever be available to them.

If, however, becoming productive in a hyper-specialized, knowledge-based economy entails 16-30 years of dependency, 10-24 years of which are devoted to resource-intensive education, then you may not have the resources to afford two children, let alone five or seven. The US Department of Agriculture estimates the cost of raising a child born in 2015 at $233,610. Crucially, that is the cost for raising children to age 17 and does not include college education and job training, nor the provisioning of young adults until they become net surplus generators. Nor does it include the opportunity cost – borne mostly by women – of parents who take off time during pregnancy and earliest infancy.

The high cost per child in places like the US might partly reflect overly generous consumption. There’s some truth to that. But the fact remains that when labor becomes hyper-specialized and knowledge-based it requires more resources to get to the point at which you become productive. It’s not just the basic needs and education. The more specialized and the more knowledge-based the economy, the harder it becomes to objectively measure whether someone has acquired knowledge and skills. Effort and resources go into signaling: prestigious degrees, resumé-padding activities, exclusive networks, fine clothes, all the things that might be subsumed under that horrid but real concept of a “personal brand.”

Raising the next farm hand or coal miner simply did not take the same amount of resources as raising the next oncologist, robot-plant operator, or social media influencer.

Pro-natalist economic policies like tax breaks and subsidies have been tried in many countries. They rarely and barely move the needle. And it’s not hard to see why. Having one to two kids on average is as much as we can afford on average.

The root cause is ultimately not that people don’t want to have children. The root cause is the amount of investment it takes to get children to be productive in the high-technology, hyper-specialized economy.

Insofar as “more technology” increases specialization and increases the need for learning, it may not contribute to the solution of inadequate surpluses. It cannot be a default answer to the problem.

Age or skill obsolescence?

The adult worker gets squeezed at both ends. With a bit of poetic license: She has to work and scrimp for 50 years to raise her child through 25 years of education to become the geriatrician she then has to pay to keep her parents alive during 25 years of retirement.

When our pension schemes were devised, they assumed people would be net surplus providers until around 65, then live off the next generations’ surpluses before shuffling off their mortal coils at around the biblical three-score and ten years.

Yes, people now live longer. And not just that: They haven’t magically started to live longer. They live longer because we’ve unlocked ways to keep people alive longer. Those medical technologies are miraculous. But they also consume massive amounts of resources and labor. My father had a medical procedure that could have extended his lifespan by a decade or two but that cost somewhere close to the median after-tax annual salary. In his case, it failed, sadly.

Rather than retirement being a phase of reduced consumption, it often involves an intensification of consumption. Peering beyond the veil of money to the underlying real economy of goods services: We train and provision geriatricians and oncologists who might otherwise have become schoolteachers and carpenters.

Historically, however, old age did not mean you stopped contributing. You shifted your contributions from, say, hunting and gathering, to childcare and cooking. That’s what freed others to do the surplus-generating hunting and gathering. And childcare meant imparting the skills and knowledge required for children to become net surplus producers. Or knowledge about how to survive once-in-a-lifetime ecological crises.

Age is not the problem. The problem is living beyond the obsolescence of your skills. As technology changes, the skills and knowledge you acquired when you were young – the ones that enabled you to generate net surpluses – are now likely to become obsolete in the span of your lifetime. Sometimes more than once.

In some professions, it is possible to retain a high enough level of productivity to be a net surplus generator past age sixty-something. But probably not in the majority of professions. Whether you “retire-in-place” and still pull a salary, or spend time retraining to become productive in another domain, you are de facto benefiting from others’ surpluses in that moment. Through no fault of your own.

In a world in which technological obsolescence and global labor specialization can destroy your community’s economic foundation overnight, working adults have to be mobile. So the option of shifting from direct surplus generation to indirect support by providing childcare is not open to every retiree. And even if it is, many of the life skills he has to impart might as well be from the Stone Age.

Demanding that people work past 67 is likely to be as ineffective as tax breaks for having more children. As for lower fertility rates, the real root cause is the rapid pace of technology-enabled labor specialization.

Misled by nostalgia

We face interlocking constraints that are both causes and effects.

- The resources and time required to become and stay productive are increasing.

- People live longer past the obsolescence of their skills.

- The horizon over which our skills are valuable is decreasing.

The dependency ratio – even in its elaborations – does not capture the reality of our predicament if it is not weighted by the intensification of child-rearing and eldercare, and the risk of obsolescence.

It’s a largely unchallenged dogma that technological and organizational innovation solve more problems than they create. However, we may have passed a point where that’s true.

Much of what we believe is rooted in nostalgia about the period known as the post-war boom known in France as the Trentes Glorieuses (“The Thirty Glorious [Years]”) and the Wirtschaftswunder (“Economic Miracle”) in Germany. Whether we experienced it directly or not, that period has shaped our collective consciousness. It birthed youth culture and rock’n’roll, and all the values, beliefs, and expectations we hold onto, no matter where we fall on the political spectra.

But the Trentes Glorieuses were an anomalous happy optimum where:

- The investment in skills required to become productive was not too onerous, meaning children became net surplus generators more quickly.

- Because children became net surplus generators more quickly, people could also afford to have more of them.

- You could count on your stock of skills to see you through 40-50 good years of surplus generation without becoming obsolete.

- People did not live for decades beyond the obsolescence or deterioration of their skills.

In contrast, now we face a world in which technological innovation extends our lives at great material cost, while rapidly rendering obsolete the skills we so heavily invested in. Both factors impose a set of constraints such that we can invest only in one or two children, if any at all.

We face this predicament globally, though its urgency will hit different countries at different speeds for historically contingent reasons.

“More technology!” is the answer for many: Make the fewer and fewer people more and more productive thanks to machines and AI. But if AI actually undermines skill development faster or more deeply than it augments human ability, the calculation will not work out.

But that is another essay and will be expounded another time.