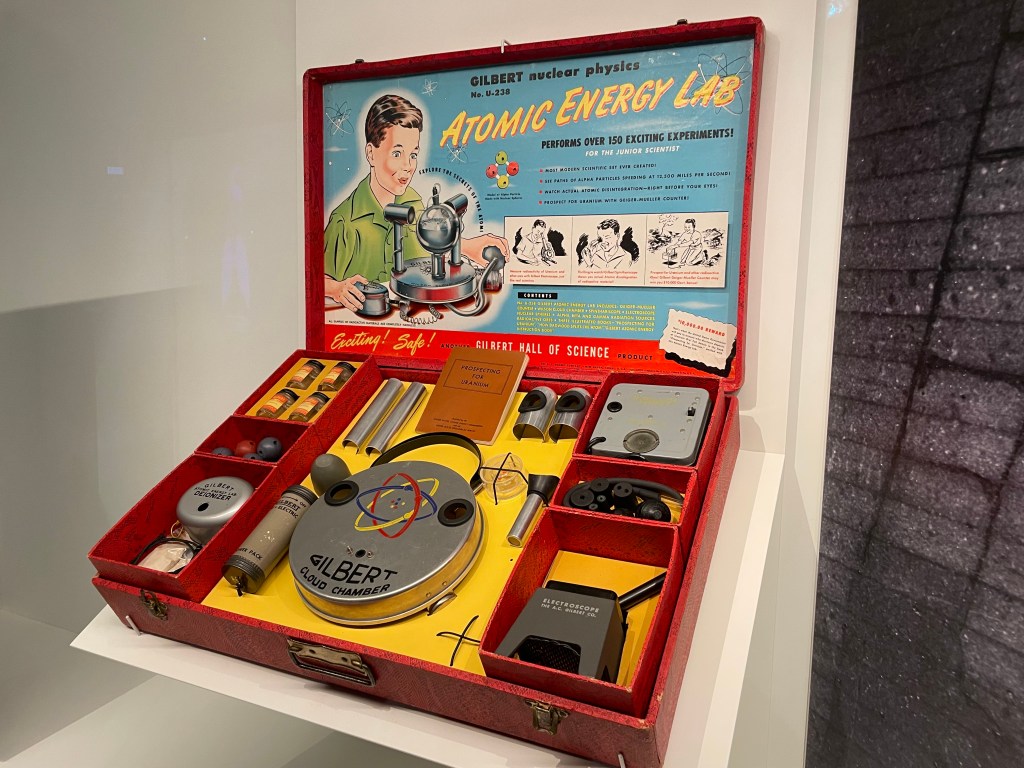

My daughter and I got a kick out of this relic at a visit to Munich’s technical “Deutsches Museum.”

It’s basically a chemistry set for hands-on learning about nuclear power. Including radioactive material.

According to the description, this 1950s “toy” was created to spark interest in science generally and specifically in nuclear power, the promising new technology that would unleash our potential thanks to unlimited cheap energy. The box advertises the US government’s $10,000 reward for the discovery of new uranium deposits and includes instructions on how to prospect for uranium ore.

The Atomic Energy Lab was not commercially successful for a variety of reasons, safety concerns not being high on that list. Still, we did not all grow up tinkering with uranium, de-ionizers, and cloud chambers as we prepared to become nuclear engineers. Safety concerns eventually limited how far we developed nuclear technology and how widely we used it. We certainly didn’t put it in under every Christmas tree or advertise it during Saturday morning cartoons.

We make choices about what technology to develop. We make choices about if, when, and how to make technology available to our children. There is nothing inevitable about the march of technological “progress.” There is no destiny to the direction it marches in. When we’re told technological progress is inevitable, that’s an act of persuasion. Believing it is an act of surrender.

Nuclear power is particularly instructive because it has not been an either/or choice. Different countries have taken different approaches. In some, advance has accelerated, in some slowed or reversed. There has been enormous internal political pressure to develop it both for peaceful and for military purposes. There has been enormous external political pressure to prevent rivals, even allies, from developing it for either purpose.

It’s also not a given that we made the “right” set of choices about nuclear energy. There is no obviously correct choice. Maybe if we had all grown up playing with the Atomic Energy Lab, and more resources had flowed to nuclear technology – as they did, for example, in France for many years – we’d have had a few more incidents and moderately higher rates of cancer for a few decades. But with all that tinkering and fired-up imagination we’d already be using near limitless clean fusion energy and wouldn’t be facing a fossil fuel-driven climate crisis. We placed bets. We mitigated some risks and embraced others.

We’re in the process of making a choice to develop generative AI with few restrictions on who uses it, how, when, and for what purposes. We’re putting these little virtual labs into children’s hands. As with the Atomic Energy Lab, we’re not terribly worried about what long-range impacts they might have on our budding scientists.

Somehow, we’re finding the will to invest in a massive reconfiguration of our electrical power generation infrastructure in the service of generative AI, with funds that seemed impossible to find when it came to transforming that same infrastructure with a goal towards sustainability and energy independence. In fact, the generative AI’s voracious need for electrical power is forcing us to reconsider the choices we made around nuclear power.

The choices we’re making are political in the best sense of politics: The mechanisms of collective decision-making we turn to when the win-win solutions of economics aren’t on offer. In the rollout of generative AI, there will be winners and losers. Whether we’re conscious of it or not, we’re in the midst of the negotiation about who reaps rewards, who bears the burdens.

As the nuclear power example illustrates, we have the power to choose. The notion that “technological progress is inevitable” is neither a logical nor empirical truth. It’s a strategic negotiating bid in the political battle about what role generative AI will play, and who will benefit from it and who will lose.